Smartphones are our banks, shopping centres and entertainment. They’re also the gateway to our personal lives and information.

And just one thing allows software applications (apps) to get hold of our personal information; our approval.

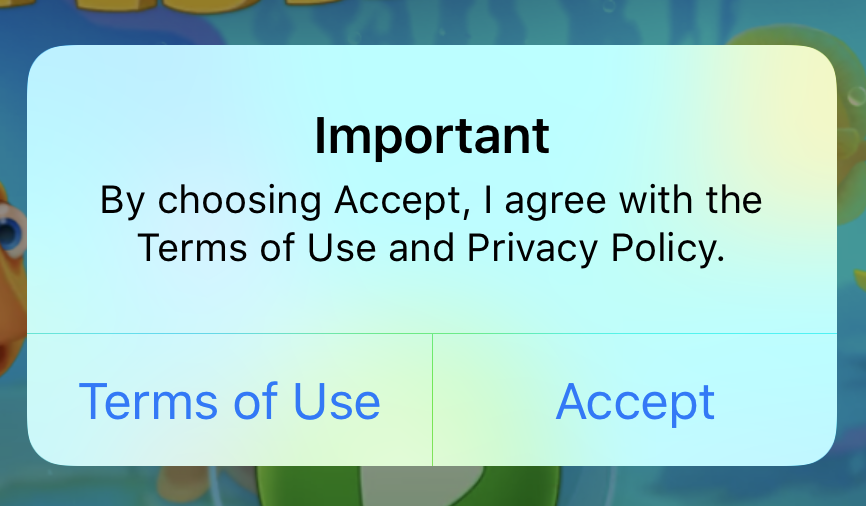

By downloading a variety of apps – from a personal budgeting app to gaming apps – you, the user, have clicked “allow access” to your location. You’ve probably not even read the terms and conditions you’ve automatically ticked.

According to Sri Madhisetty, lecturer and part of the team behind the Magic Lab at Sydney’s University of Technology, mobile users are forced to trust and agree to terms and conditions when downloading an app – even if they don’t understand them.

“The concept of consent is not very clear”, he told Hatch. “There is a lack of awareness… about the dangers that can happen.”

For instance, The New York Times discovered 250 gaming apps are using the software Alphonso, which enables the microphone in your mobile phone to collect audio signals in TV ads and shows. The data is then used in targeted advertising.

There are actually three major parties with a vested interest in your personal information; app developers, government policy-makers and third-party software developers.

Government policy-makers

App privacy policies frequently refer to “personal information.” The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner defines this as: “information or an opinion about an identified individual, or an individual who is reasonably identifiable.”

Examples include name, signature, address, telephone number, date of birth, medical records, bank account details, employment details and commentary or opinion about a person.

There is also “non-personal information” which does not identify the user.

This information is collected during the use of an app and is explained in privacy policies as being necessary “to improve product, services and content”.

According to the government’s Mobile Privacy: a better practice guide for mobile app developers, there are six essential steps to protecting a user’s privacy:

- A privacy management program

- Privacy policy

- Obtain consent

- “display user privacy settings with a tool that allows users to tighten their settings. The tool should be easy and straightforward to use.”

- The timing of user notice and consent is critical.

- Only collect personal information that your app needs to function.

- “the Australian privacy policy requires that you only collect the personal information that is necessary. Consider whether you need to collect personal information at all.”

- “Don’t collect personal information just because you believe it may be useful in the future.”

- Secure what you collect

Now knowing these essential steps, are we seeing them in the mobile apps we’re downloading?

Mobile apps developers

Kids Learn and Play, have games specifically targeted to children – like Snake Tales, Zap Ballon and City Runner. Their privacy policy states: “We may collect any personal information. Some of the KLAP Edu-tainment apps are integrated with Alphonso Automated Content Recognition (“ACR”) software provided by Alphonso, a third-party service.”

This is an example of “non-personal information” being gathered by an app through a third party .

But when you download Snake Tales and Zap Ba there’s no prompt to tell the user of this information is collected. It goes straight to the game.

Moneysoft, a budget and money tracking app, connects to your bank accounts and is described as a platform providing a “single dynamic view of real-time, complete financial data.”

Its privacy policy states: “we only collect personal information about you that you provide to us”, and goes on to explain that the user doesn’t have to use their real name but has to provide a real email address.

When this information is collected, Moneysoft, also advises that your personal information “may” be disclosed to others: “Agents and contractors who supply services to us (e.g. companies that send emails, external data storage providers and marketing firms).”

Sri Madhisetty says consumers need to be see a clear privacy framework if they’re to trust developers.

“Control has to be happening at the phone side… build trust, up front,” he said.

“The [information] has to be given very clearly to the consumer of what third-party means.”

Software developers

At this point, there is another question users need to ask. What does the software developer do with the data collected?

Alphonso’s privacy policy states they may use it to: “Analyse user trends and behaviours… to generate reports…

deliver marketing materials on [our] behalf and for other third parties, that [they] believe are relevant to you.”

This means they aim to collect data for marketing purposes, to then target the user with specifically tailored advertisements.

Alphonso states that the user is able to “withdraw consent” from “the service” and provides an “opt out guide” on its website.

How much do we really understand?

Knowing now what lies within the privacy policies of smartphone apps – what can users do to protect their information?

Mr Madhisetty says it comes down to communication. “There is a lack of awareness amongst young people,” he said “[so] create a certain awareness.”

Ultimately, other than refusing to download apps, the best plan of action is for users to become aware and informed.

– Emma Kosowski